In a rural village outside Salem, India, Dr. Siddharthan tried to persuade Shanthi that he could successfully perform the needed eye surgery on her young son and make him see for the first time in his life. “I will send Samuel Stevens to the village and pick up you and your son. He will bring you to the eye hospital. Everything will be fine. Can you imagine how happy your son will be when he sees his mother for the first time? And the whole village will rejoice when they see the great miracle.”

“No,” said Shanthi softly as she lowered her head and stared at the ground. "I want my son to see, but the people of my village will not hear of any such thing. They have warned me that if you put a new eye into my son’s head he will be forever cursed, I will be cursed and my other children will be cursed.” Shanthi began to shake with fear. “My villagers demand that they like my son just as he is … blind. They want to take care of him all of his life. When he needs them to help him walk or eat it makes them feel very good and important. They want him to depend on them forever. They will not allow me to bring my son to your hospital.”

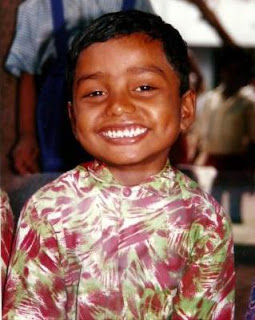

It was decided by Samuel Stevens and Dr. Siddharthan, however, that the day before the surgery Samuel would drive to the village and try to persuade Shanthi to allow the surgery to take place on her son. I was invited to go with Samuel and meet Shanthi and the villagers. When we met with Shanthi she began to cry openly. The previous night she had a dream. She saw a man come and take her son away and later he brought him back to the village … and he could see! She had never seen Samuel before but he was the exact man who had come in her dream for her son. “I do not need to come with you” she said. I know that when I see my son again he will see perfectly!”

And indeed, when he returned to the village, he could see perfectly. Oh, what a day of celebration!

On my airplane ride back from Salem and Coimbatore to Madras, India, I began to search my own heart. “Are there people or situations in my life where I am encouraging unhealthy dependence?” The villagers wanted Shanthi’s son to stay blind because it made them feel good and needed. What a tragedy that would have been. Who or what in my life do I need to relinquish in order for someone else to become healthy.