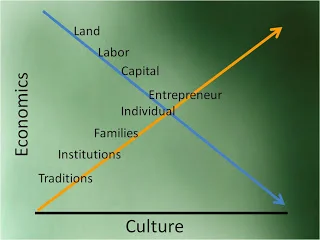

Transformation takes place at the intersection of culture and economics. Where any of the economic components, e.g., land, labor, capital, and the entrepreneur intersect with such components of culture, e.g., traditions, institutions, the family, or individuals, you will probably find transformation taking place. In fact, you can, no doubt, predict that transformation will take place at that intersection. The American farm policy example, between the 1930s and the present, fits the Cultural Economics matrix perfectly:

Land use was intersecting with traditions. Traditions were intersecting with labor. Components of capital were intersecting with institutions; families were intersecting with everything, etc. This transformation was taking place on no less than six million family farms in America and affecting twenty-five percent of the voting population of the country. By the 1990s, less than two percent of the families still lived on the farms. It seems appropriate to ask, why did they leave? Where did the people go?

Some of the farmers simply got sick and tired of the government’s interference and moved on. Another reason for leaving the farms was that the small family farms had been an easy and convenient entry threshold and starting point for newcomers to America. As other American resources began to be developed, new job opportunities opened up that lured folk away from the family farm.

At the same time agricultural land values began to increase. As soon as the government began offering to pay for crops that farmers didn’t plant, many farmers began offering to buy their neighbors’ acreage so that they could ‘not plant crops’ on their ground, also . It only made economic sense. Then investors began to formalize corporations and purchase lots of fertile ground to qualify for the strange program in a larger way. Competition to purchase the ground began to drive the land prices even higher, making it a good time for the small farmers to grab their chance to sell, take their proceeds, and find a place in town close to a good paying job.

Land prices got a boost from another odd set of circumstances. Earl Butz was the Secretary of Agriculture from 1971 to 1976 under Nixon and Ford. It was his intent to drastically change America’s farm policies and reengineer some of FDR’s socialistic farm support plans. He soon abolished some of the programs that were paying the farmers to not raise crops or livestock. He was bent on expanding and increasing farm production and allowing the farmers to have a say in what crops they would plant. His exuberant theme to the agriculture business community was to “get big or get out.” He also beat the drum for the farmers to plant their crops “from fencerow to fencerow,” to increase their yield rather than cut back on production. (1)

That message was all that the corporations needed to hear. It sounded a lot like a policy shift back to the direction of a free enterprise agricultural model. It was a green flag to the land consolidators to increase in size and scope their involvement in the agriculture opportunities. Land prices surged and more small farmers grabbed the opportunity to make a profit by selling their land and leave the farm. Agriculture Secretary Butz proved to be a poor choice, however, to represent the Republicans’ attempt at farm policy reform. After two separate incidents of reprehensible verbal gaffes, Butz was pressured to resign his cabinet post in 1976. Later, he pleaded guilty to federal tax evasion. But the big corporate farms were there to stay.

From that point, however, the progressive, centralized government folk unleashed tremendous pressure to stymie any such free enterprise encroachment in the agricultural administration. And as we learned last session, The Freedom to Farm Act was sufficiently gutted, and the Farm Act of 2002 reinstituted the direct-payment provisions, and the “automatic emergency aid” provisions of the law were guaranteed annually whether there were any emergencies or not. That which had started out towean the farmers off unnecessary subsidies ended up entrenching the farm controls even deeper.

The government began to realize that having the corporations on the farm land could be far more politically advantageous than dealing with the individual farmers, especially where the individual farmers had been virtually marginalized by dwindling numbers. The government simply continued the subsidies and above-equilibrium price programs. The government and the new corporate farm operators became strange bedfellows. Together, they were able to utilize the rich fertile earth to produce big money for each institution, instead of just food crops for the nation. Hand in hand they walked together, reaping enough money to supply both the corporate institutions as well as the enormous agricultural bureaucracy. The land was now growing money, and not just food crops, through price controls and the ability to raise billions of dollars in tax revenues from the massive numbers of non-farm citizens.

To simplify this issue, let me tell you about what the economists call Public Choice Theory:

Farmers producing a particular crop (or, for that matter, this can be true for labor unions or any other group in an industry) can use political means to transfer income or wealth to itself at the expense of another group or of society as a whole. It is also possible for a small group to receive large benefits at the expense of a much larger group whose members individually suffer small losses without really ever realizing it.

For example, a group of grape growers or sugar beet farmers would organize and establish a powerful and wealthy political action committee (PAC).The purpose of the PAC would be to transfer income or wealth to the group through their efforts of promoting or soliciting government programs. One of their methods would be to aggressively lobby senators and representatives for their vote on price supports, tariffs, or quotas that affected the group’s products. Once the PAC secured the legislator’s vote, the PAC would reciprocate by doling out large political contributions to the participating politicians, who would otherwise have had nothing to do with the grape growing or sugar beet industries.

It is also possible for a special interest group to vigorously lobby and increase its own income at the expense of the ordinary citizens. Very large sums of money desired by the special interest groups can be collected from each individual citizen through collected taxes. Those citizens may never even become aware of being taxed. Busy taxpayers are not likely to be informed about the costs of government programs for the sugar beet industry if they have no formal connection with it. The taxpayer, subsequently, doesn’t even know enough to object about his legislators agreeing to support subsidy measures for a certain commodity. The special interest PAC group would receive little or no objection to their solicitations.

Let me quickly share one more political means of transferring wealth of a nation to groups that benefit at the expense of a much larger group, whose members individually suffer small loses. Trading of votes on governmental policies and programs is referred to by politicians as Political Logrolling. It is designed to perpetuate government programs and subsidies by special interest manipulation. For example, one senator agrees to vote for a subsidy program that benefits another senator’s voters. That senator then returns the favor by voting for a measure that benefits the first senator. One politician may vote for expanding the school lunch program and proffer his vote for a direct payment or subsidy for sugar beet growers, even though no sugar beets are grown in his state. The vote trade may not benefit his constituents, but have a lot to do with financing his next campaign to get reelected.

Companies that supply agrochemicals, farm machinery, farm insurance programs, and hundreds of other farm industry items are willing to support PACs as well as lobby for a generous menu of government subsidies and direct benefits to the farmers, be they individual or corporate. It furnishes them with more money to purchase farm related goods. Additionally, the tens of thousands of people who are employed by the government to service and administer the Department of Agriculture and its subsidiaries are highly supportive of political means of transferring wealth from the taxpayers to their monthly paychecks. Over sixty million dollars are spent for just agribusiness people to lobby our legislators each year. (2)

Those practices help to explain why farm subsidies are so entrenched and why the food stamp program, for example, expanded for so many years. But the simple fact remains that misappropriated natural resources and the loss of free cultural and economic choice make a nation poorer rather than wealthier.

Next Week: The Improbable Experiment

(Research ideas from Dr. Jackson’s new writing project on Cultural Economics)

© Dr. James W. Jackson

Permissions granted by Winston-Crown Publishing House