Congo: Wednesday, February 4, 2004

I was up at 5:30 a.m. and ready to meet for breakfast with all the medical doctors and hospital department heads. It was good to also be traveling with the president of Congo’s Covenant Church and the medical director of all the northern part of the Democratic Republic of Congo.

Our touring part of the assessment took us until 12:20 p.m. Following lunch, I had group and individual meetings with the leaders of Karawa. The Karawa Township had about 350,000 villagers tucked away down jungle pathways. Plus, people traveled on foot for many days to get to the Karawa hospital for help. There were five doctors stationed at the facility along with 35 nurses. Only about 50% of all the patients could pay any amount of money toward fees for their help. Some patients' families stayed at the hospital to work to pay off their medical bills. The Congolese government paid nothing to support the hospital or the 48 rural health clinics that fed patients into the hospital. In fact, the government would send its soldiers to Covenant Church clinics and hospitals in expectation that the church would cover all their expenses.

The Karawa hospital was the largest of the hospitals I visited but was totally pathetic. Again, as with the hospitals in Loco and Wasolo, they were trying to make their own IV solutions out of poorly filtered water that was in no way sterile. They desperately needed a new 20-kw, electric generator to cover their “current” needs. They needed almost everything for their surgery room and there was not an EKG machine, ultrasound, defibrillator, sterilizer monitor, ventilator, centrifuge, cauterizer, working x-ray machine, lead apron or gloves or good microscope anywhere in sight. They were washing all the surgery gowns and contaminated surgical drapes and sheets by hand in an open tub. I thought, as I viewed, “my God, we have so much excess and these people have absolutely nothing!”

But I knew down deep inside me that God loved those village people as much as he loved my successful sons and it was imperative to help them in their need. They had an old autoclave someone had given to them. But it had not worked. So, the maintenance people had stripped everything from the outside of the autoclave down to the pressure tank, then adapted it so that they could set it in a pit of hot charcoal to get it hot enough to steam. It did not thoroughly sterilize even the operating room instruments.

When I had walked the halls and different wards I noticed a four-year-old boy whose shirt had been ignited by an open cooking fire. The shirt had stayed on him and burned him. He was sitting upright in an old dirty bed with no sheets underneath a makeshift mosquito net. His mother was sitting close by trying to comfort him but the hospital had absolutely nothing to treat a burned child. He would probably die in a few days from infection. The mosquito netting would certainly not be enough.

Another teenage boy was in a filthy bed. They threw back the covering over his lower leg. He had a tumor below the knee. His lower leg was as big as his thorax and almost impossible to move. “He is not strong enough for us to try any kind of surgery so it just keeps getting larger,” said the doctor who was with me.

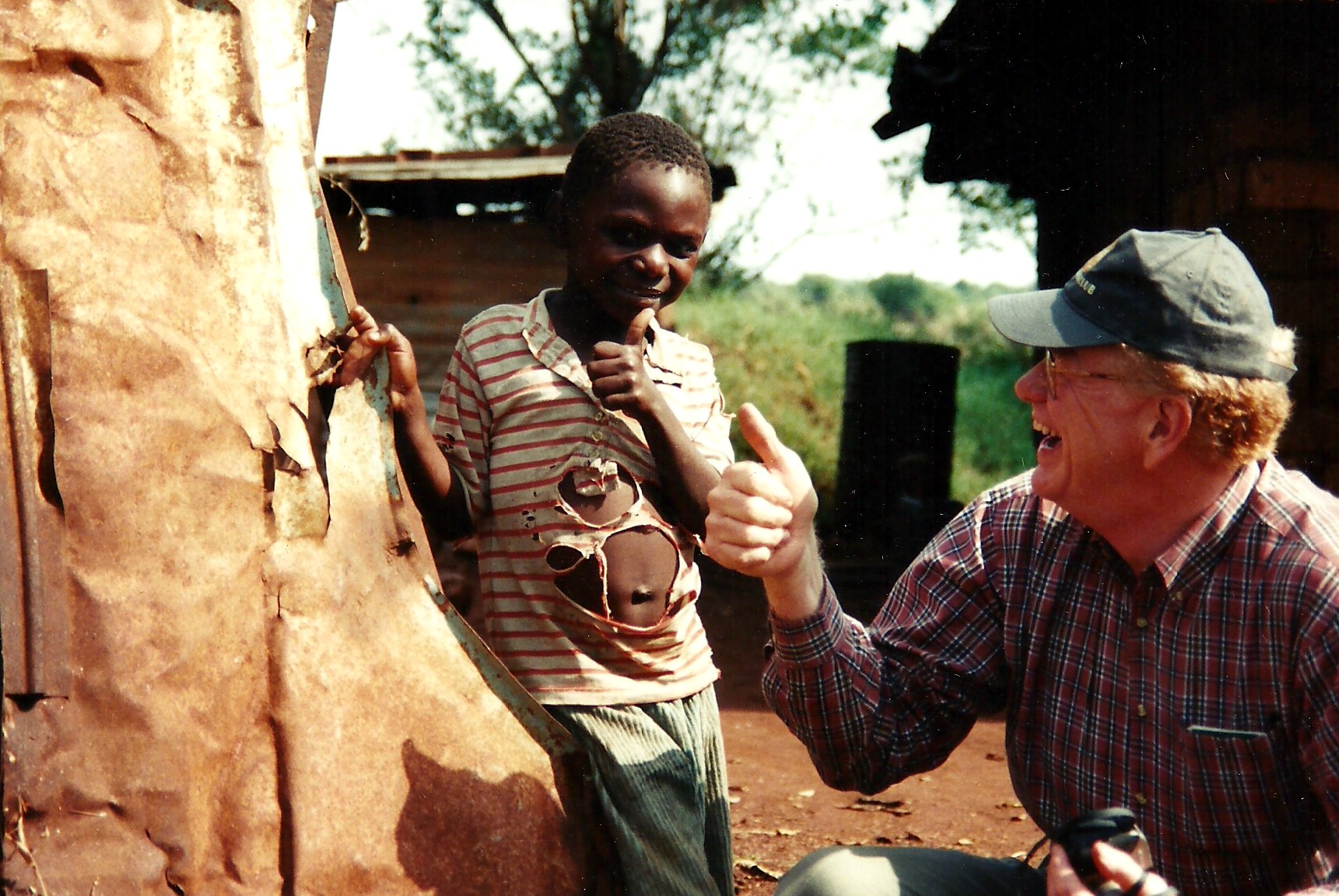

At one time the Karawa compound had been a thriving community. Then wars came and even people like the Gustafsons and many of the medical staff had to leave the country. Now they were returning, including Keith and Florence Gustafson, to try to help strengthen the needed facility. That was why Project C.U.R.E. was there.

As I returned to my mosquito-net-enshrined cot and my rusty water and plastic dipper, I reflected on my experiences at the three different Congo hospitals. Nowhere else in my 17 years of Project C.U.R.E. had I seen hospital beds so disgustingly filthy, or walls, floors, and ceilings that so desperately needed paint to cover the dirt.

There had not been one working monitor in all of northern Congo. All doctors, nurses, and medical staff personnel were indigenous workers who were discouraged to the bone. The only defibrillator I had seen was a monstrous contraption that looked like an electric execution machine out of a Cambodian torture prison (fortunately the thing did not work).

At my final meeting with the doctors and head nurses, I made them promise that if I sent them pieces of medical equipment for their hospital they would be trustworthy in throwing out all the old “prehistoric” pieces of equipment that had not and did not work. Together we would start on an adventure of hope and pride and together we would push for excellence and significance at the Karawa Hospital. They loved it! The president of the Covenant Church of Congo, Rev. Luyada, the medical director of the zone, Dr. Mbena Renze, and the hospital chaplain all appreciated it immensely!

Thursday, February 5

I was up at 4:30 a.m. Sam and Rod, our MAF pilots, would be ready after breakfast to take us on our long airplane ride back to Kinshasa. Keith Gustafson stayed at Karawa so our first flight segment back to Gemena was to drop off Rev. Luyada. At Gemena we picked up two paying passengers who needed to get back to Kinshasa. They were two US embassy workers who had been out to Gemena studying the possibility of placing some grants and loans for development in the area.

We flew another seven hours in our cramped Cessna 206 jungle flying machine, stopping once to refuel at a MAF base.

At the Kinshasa airport I met up with another MAF pilot who had helped me on my previous trip to Congo. After hanging around with the pilots while they refueled their planes and tied them down, just outside Kinshasa’s main terminal, the three of them took me back to their headquarters office. It was in the same building where Larry Sthreshley had his office. As we drove up Larry came out to greet me. He had insisted that I spend the night with his family before going on to Cameroon.

However, Rev. Mossi and Mr. Ndimbo, my official Covenant Church hosts, said that Martin had stayed home from her law school classes all day to prepare dinner for me. So, it was agreed that I would go to Rev. Mossi’s house for dinner then they would take me to Larry’s home to stay the night.

The Sthreshleys and I stayed up into the night discussing my previous visits with them in Denver, in Younde, Cameroon, and Douala, as well as Kinshasa.

I can’t tell you how nice it was to sleep in a house with some cool air, clean sheets on a regular bed, and real lights and nice warm water from a pipe in the clean shower stall. It all felt so good.

© Dr. James W. Jackson

Permissions granted by Winston-Crown Publishing House