(Journal: L’viv, Ukraine: September, 1999) Lloyd and Biggy wanted to keep pressing on. We next drove to a very poor part of L’viv, where they wanted to show me a soup kitchen they established for orphans who have been left on the streets to fend for themselves. The soup kitchen was on the back side of a blockhouse complex, up on the second level. The small space included two rooms and a hallway. One room was where they cook the soup. Women were standing, tightly squeezed, between two stoves. On the stoves were two caldrons of steaming carrot, onion, and beet soup. In the hallway, two old women sat on stools scraping clean the vegetables to be dumped into the soup.

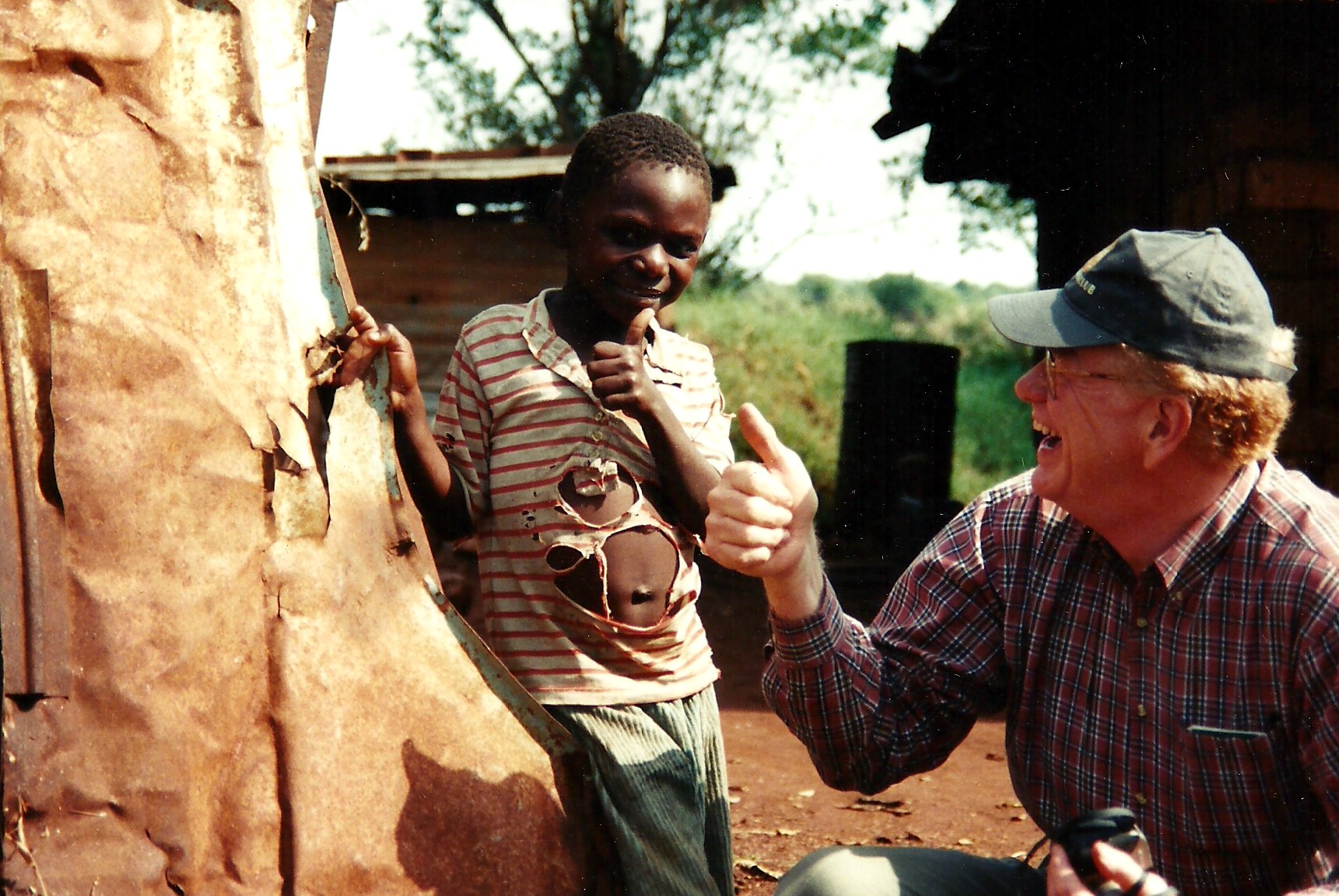

A high-energy, short Ukrainian fellow named Meeche is in charge of the soup kitchen. How he ever gets fifty kids packed into the other room challenges my imagination. But he showed us how the stray kids not only eat there for free but also gather consistently to sing religious songs as Meeche accompanies them on the guitar.

Biggy left us at the soup kitchen, and Lloyd and Meeche took over the tour from that point. Meeche asked if I would accompany them to the prison. I agreed. He quickly walked to the kitchen and grabbed a long, plastic-handled knife. In the small hallway, he stopped to sharpen the knife on a stone.

I couldn’t resist chiding Meeche for being crazy enough to think they’d let him into the prison with the long, sharp knife. He just laughed as he stuck the knife into his little canvas bag.

In a lower part of downtown L’viv, Meeche pulled his old station wagon over to the curb and then motioned for us to follow him. He grabbed a very large cardboard box from the back of his wagon. We went down the block and around the corner to the left. Then we took two steps down from the sidewalk and right into a state-run store—a leftover relic from the Communist days. People were jammed into the store, pushing and shoving to get to the counter.

Meeche talked to the extremely unmotivated woman in her old, state-issued, dirty smock behind the counter. She was so obviously used to saying no that her head was shaking no even though she agreed that Meeche could buy some government-subsidized loaves of bread. He had her give him enough loaves to fill the large cardboard box, and then he purchased a case of packets containing about two cups of sugar each.

With our treasures, we paraded back to the station wagon and climbed back into the vehicle. Meeche backed up across the street and positioned the station wagon right in front of a couple of solid-steel gates. Soon a stern-looking uniformed man with a gun came out and opened the frightening gates for us to drive through.

When Meeche had parked the car earlier, I had noticed the tall walls on one side of the street, which stretched the length of a couple of blocks. But I never realized that it was the site of the old prison we would be visiting. But once inside the outer gates, there certainly was no question that we were in a very secure prison. On the inside walls were guard posts and razor-wire fences.

When we stopped, Meeche jumped out of the station wagon and popped open the back doors. He reached into his canvas bag and proceeded to whip out his long, sharp knife. I was hoping the guards wouldn’t shoot him on the spot. But they just stood around and watched as Meeche pulled out the large box of bread and began cutting the oblong loaves into four pieces each. He then gave the pieces to Lloyd to stuff into a large, green, plastic bag.

Quite a group of guards had gathered by that time. I had my brown camera bag slung over my shoulder and had taken pictures of the store where Meeche purchased the bread, as well as the large steel gates of the prison. Meeche told me the guards would definitely not allow any photo taking inside the prison. I certainly could understand the reason for that. Lloyd said he once got a few feet of video-camera footage before they shook their heads at him.

When the bread was all cut and sacked, and Meeche and Lloyd picked up the case of sugar along with miscellaneous sacks of candy, the entourage of guards accompanied us across the open compound toward a steel door with bars. We went up about four steps into a dirty waiting area that was tightly enclosed and had a dirty service window on one side. There, we were asked to shove our passports through a crack under the glass.

Once our passports were checked, a heavy door at the other end of the room clicked, and the front guard ushered us into a long hallway with steel-bar doors on either end. After going through another secured hallway, we entered an open courtyard. The smell as we walked outside was strong enough to gag me. On the other side of the courtyard, we walked past a cage that held big black guard dogs. Another solid steel door opened in the middle of a wall, and we entered with some guards in front of us and some guards following us.

Our pace was slowed because we had to follow two other guards up a flight of stairs as they accompanied a prisoner back to his cell. The prisoner was about twenty-two years old, could hardly move one foot in front of the other, and looked like death warmed over.

Once on the second floor, we were introduced to the prison nurse, and she invited us into her clinic. She was a short, hardened woman in her early fifties, and her hair was a weird shade of peroxide blonde. But her kind eyes surprised me. I immediately wondered what kind of woman would be a nurse in an old Communist prison, where she had absolutely nothing available to treat her treacherous patients.

Next Week: How Do You Deliver Hope in Ukraine?