Dr. Heraldo Neves:

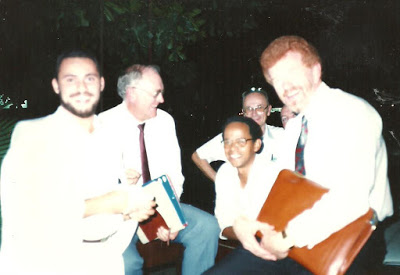

One day, quite separate and apart from Lorena’s family activities, I visited a little doctor in an area just outside Rio de Janeiro called Mesquite. I had met the fellow earlier and he had invited me to come and see what he was doing to help the people in a populated area of about 300,000. Previously, there had not been any health-care facility in the whole area, but Dr. Heraldo Neves and his friends had purchased an old house and had converted it into a very humble clinic.

When I arrived, I was startled at what I saw. There were hordes of people gathered in the hot sun crowding their way toward the front door of the old house. Mothers were holding crying babies, and old ladies were waiting their turn to get in by resting up against the building, where they could find a splinter of shade. Many people had been there since early morning waiting to see the doctor. He was their only hope for medical attention for their babies and for themselves.

Dr. Neves would try to persuade his other doctor and nurse friends in Rio to volunteer and come out to his clinic and help him meet the overwhelming need. As I approached the front porch area of the old house, I saw an ancient dental chair and drilling apparatus that was run by foot pedals and frazzled cables. That was Dr. Neves’s dental clinic.

As I entered the door, I looked to the right at a room that had once been the front bedroom. It was now painted a light blue color and had a poster of a baby pinned to the wall. On a rickety old table there was an old rusty set of baby scales. That was Dr. Neves’s pediatrics ward. What had once been a kitchen was now the emergency room that consisted of a canvas cot, an empty canister of oxygen, and a small metal cabinet with a glass front. I could see that re-rolled, grayish bandages were stacked inside the cabinet. That was it. That was Dr. Neves’s health clinic.

“I don’t get it, Dr. Neves,” I said. “What is your problem here? You have all these people outside in lines that seem to stretch for a city block. They have come here thinking that you can help them, but when I come inside I can see that you have literally nothing in here to help them. Please tell me in your own words, what is your problem? Don’t you have anyone who comes here and comes along side of you and helps you? Doesn’t your government help you?”

Dr. Neves was a short man with a high energy level and dark penetrating eyes. He looked straight at me and said, “Meester Jackson, you are the economista, you should know that we are experiencing inflation that is running over three thousand percent. I have no money, but even if I did I could not buy anything from the US or Great Britain or Japan. We are not allowed to buy anything outside Brazil, since our cruseiros currency would then flow out of our country and into the other country, causing more hyperinflation for us. And the government infrastructure here is not strong enough to help us. So, we are doing the best we can with what we have.”

“Dr. Neves,” I confessed, “I do not know what I am talking about when I say this to you. But, I think I could go back to where I live in Colorado and get some medical supplies donated to help you.” Then I quickly added, “But if I were able to send some things to your clinic, you would have to guarantee to me that the goods would not get into the black market. I have been here in Brazil now long enough to know that I want to be part of the solution and not part of your problem.”

The intensity of Dr. Neves’s countenance softened and he said to me with a little smirk to his smile, “Well, Meester Jackson, you are working directly with President Sarney in Brasilia; why don’t you get the guarantees directly from him?”

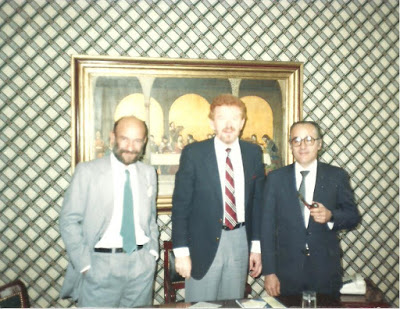

Dr. Mauro Corbellini and President Sarney:

I got on the airplane and flew back to the capital. I took Lorena with me to do the translating so that there would be no misunderstanding. There I began working on a medical donation concept with the President and Dr. Mauro Corbellini, Brazil’s Minister of Health. In our meetings the Minister of Health said to me, “if you will go back to the US and obtain donated medical goods for Brazil, I will see to it that you can import the things on a tax exempt basis. And, further, I will give you a large storage space on the University Medical School campus where Lorena attends in the city of Campinas. You will have the key to the storage area and you can decide where the medical goods should go based on your assessments.”

I told the Minister of Health, “Thank you. That is all the assurance I need.” We shook hands and we parted. When I got back on the airplane, I slumped down in my seat and put my hands to my forehead and thought, Oh, my goodness, what have I just done to my life? I don’t even know where to go get a Band-Aid.

I made two trips to Brazil in 1987. Our first load of donated medical goods was shipped in August of that year, along with a $5,500 cash donation from Anna Marie and me to Dr. Neves’s clinic. My trip to Brazil in March of 1987 had certainly changed my life. Dr. Neves could not afford to pay any money for medical goods. I would have to find a way to get the items donated. Additionally, the shipping costs to deliver the donations could be a humanitarian deal-killer.

How would we develop a model that could be sustainable? Perhaps pursuing the idea of financial consulting with foreign governments like Brazil would help finance the possibility of additional gifting. There certainly appeared the possibility of creating some revenue stream from trying to develop the concepts of debt-for-equity swaps and other financial ideas that could assist the Brazilian government in their financial crisis. I would push to see if the US banks would be agreeable to pursue those kinds of ideas.

The years of 1984 through 1988 were extremely busy and a bit complicated. I was not only getting more involved in Africa and South America, but I was still speaking regularly and conducting seminars with the What’cha Gonna Do With What’cha Got? project in the US. Now I had even been asked to hold two of the financial seminars in Brazil.

It didn’t take any time at all for word to get out that we had begun to donate high-quality medical goods to Brazil. Before the end of 1987, I was also approached by contacts from Guatemala, wondering if we could include them in our donations. From those early days in Brazil the growth of Project C.U.R.E. has not slowed down. Twenty-eight years later we are shipping into over 135 countries and have well over seventeen thousand volunteers helping us just in the United States. But I will hold dear to my heart forever those early days where God directed my heart, ambitions, and efforts to help the beautiful people of Brazil.

© Dr. James W. Jackson

Permissions granted by Winston-Crown Publishing House