“ENTITLEMENT” is defined as a feeling or belief that you deserve to be given certain privileges ... someone owes you something just because you are you. I am coming to believe that this “entitlement plague” is perhaps more to be feared throughout the world than malaria or dengue fever!

I have traveled in well over 150 countries and have viewed this pandemic everywhere. One day I was in the Yerevan, the capital of Armenia. I was negotiating the logistics for sending millions of dollars of donated medical goods into the country following the ravaging earthquake centered in Gyumri.

Rouben Khatchatryan was a leftover communist bureaucrat who had assumed the privileged position of gatekeeper in the new administration. Rouben was a large man with no way to stretch his brown wool suit coat around his gigantic stomach. When he laughed, the light bounced off his gold teeth and around the room like the sparkles from a disco ball. During my first meeting with Rouben, he boldly announced to me,“There is a law that says that the rich countries have to send money to the poor ones, so you must send money to me here at this address so I can optimize my region.” The only thing that was ever optimized was Rouben’s own wallet. Because of him the area didn’t stand a chance of solving its plight.

A short while later I was traveling in West Africa. It was a difficult drive from Lome, the capital of Togo, north to the city of Dapaong in the northwest corner, close to the border between Ghana and Burkina Faso. During dinner that night at the En Campment Hotel, our discussion at the table wastroubling. It became quite apparent that our Togolese friends, on average, knew almost nothing about economics, business, governance or how the “real world” works.

One of the top leaders of Togo declared emphatically, “Well, Europe and USA just have to come here and give us more money until we have enough. Someone must simply take it away from them and give it to us because we need it.” That sparked quite a lengthy discussion.

I received some great insights that night.

The whole attitude of “entitlement,” or “you owe me,” really has become a great enemy of progress and human dignity, not only in West Africa and Armenia, but all over the world, including our own culture in America. It is one thing to “graciously receive” ... it is quite another thing to “expect,” and worse yet, “demand.” Personal self-esteem and feelings of worthiness have really suffered in pandemic proportions because of this contagious plague.

Once the collective human minds and spirits of a people embrace the notion that someone “owes them something” for one reason or another, it totally changes their character and their self-motivation and the perception of their own worth. It seems to neutralize the component of “personal responsibility.” They fall into the trap of seeing themselves as “victims” and from that perspective they are totally blinded to creative possibilities within their own grasp.

Once they have transferred responsibility and accountability to someone else, and that new source fails to produce the expected answer to all their needs, then they feel a legitimate “right to blame those who failed them,” and emphatically to devote all energies to being angry and vengeful. And where blaming starts, creative growth stops! Additionally, the plague totally eliminates any exercising of true compassion toward anyone else.

Ironically, today many developing countries are endeavoring to build their future economic systems on the idea of expecting or demanding that “the rest of the world needs to step up” and give them more. And, at the same time, they are blinded to the great opportunities of independent and sustainable growth and development so near to them. Blame and greed will trump the spirit of positive initiative. Malaria and dengue fever can kill your body ... “entitlement” can kill your soul!

Strange and Unaccustomed Paths

One of the most satisfying episodes in my life was when the United States Department of State awarded my efforts with one of their highest humanitarian recognitions, the “Florence Nightingale Award.”

In the Fall of 2002, Congressman Cass Ballenger in Washington, D.C., and Ambassador Martin Silverstein from Uruguay called me and asked, “How fast can you get away and travel to Uruguay to do your Needs Assessment Study, and get some donated medical goods to that country before its economic crisis deepens into a political crisis that would be hard to reverse?” The congressman served on the International Relations Committee, where he was Chairman of the Committee on the Western Hemisphere.

I agreed to drop what I was doing, and I quickly traveled to Montevideo, Uruguay. Thanks to the help of the Embassy staff and the office of the Congressman, the project turned out very successfully, and for that I was given the coveted award. But the thrill of the ordeal was greatly enhanced by the fact that from my childhood I had been a great admirer of Florence Nightingale. When she was a little girl she wanted to be a nurse, but her family thought it to be less than dignified, considering the deplorable practices and facilities where nurses had to work at that time. But during the Crimean War in 1854, soldiers from England were sent to the front to fight. Many were wounded without any access to hospital care.

Florence Nightingale offered to go to the front. She was given the opportunity to gather up some nurses and travel to a battlefield hospital near Constantinople, in Turkey. There she discovered a most dreadful scene where nearly 2,500 British combat men lay helpless and unattended in the very worst of surroundings. The unsanitary conditions were deplorable, with open sewers and filthy clothing and blankets. There were no medical procedures or provisions available to the men, and many were dying, not from their original wounds, but from rampant disease and infection spawned from the filthy conditions.

The leadership skills of the calm, but forceful, nurse attacked not only the problems of the immediate situation, but Florence Nightingale determined to attack and change the British health care system altogether. The new female recruits organized themselves into a cleaning brigade. They cleaned out the rats’ nests, washed down the facilities, scrubbed down the patients, even to their flea-infested scalps. Nothing escaped the cleanliness of the new brush brigade. Immediately, there was a dramatic drop in the death rate in the field hospitals. The wounded soldiers began to respond well to the medical treatment. The morale jumped by leaps and bounds. The nurses’ approach had consisted of hard work and cleanliness. Even when there was no money available from the British government, Florence Nightingale went personally to donors and raised money for medical supplies and bedclothes. Some believed that she was able to reduce the mortality rate of the wounded soldiers by as much as 75%.

All of Britain declared her a heroine upon her return to London. But Florence Nightingale’s own health was in shambles. Following the war she was pretty much home bound for the remainder of her life. But she never gave up the successful fight to radically reform Great Britain’s health care delivery system. From her bed she continued to put the pressure on health officials and parliament to implement reform. As one person she was able to leverage her position and influence. She became an “Agent of Change” for the entire philosophy and protocol of the British health care system.

But the part of Florence Nightingale’s story that so intrigued me, and made the State Department’s award so special to me, was the nurse’s own quote when questioned about her accomplishments:

“If I could give you information of my life, it would be to show how a woman of very ordinary ability has been led of God in strange and unaccustomed paths to do in His service what he has done in her. And if I could tell you, you would see how God has done it all and I nothing. I have worked hard, very hard. That is all; and I have never refused God anything.”

A Badge of Love in the Jungle

Outside the airport terminal, Dr. Horner was waiting to pick me up. Our destination was San Juan Opico, El Salvador. The paradise had just come through a difficult 12-year civil war. Dr. Horner was quick to explain to me about one of the hazards of El Salvador. "The unemployed men have become bandits." He then pointed out the 212 bullet holes in the vehicle in which we were riding. Dr. Horner promised that as long as I was with him, he would try to stay away from any roads where the bandits hung out.

I was in El Salvador to inspect the new "Clinica la Esparenza" facility that Project C.U.R.E. had completely furnished with medical goods and also determine how we would partner with other hospitals and clinics in the region. It was very rewarding to see all the medical goods being moved into the new clinic and being set up. All of those items were once in our warehouse in Denver.

We drove to a village called Chantusnene. It was a typical "invasion city," like I had seen in Haiti, Colombia, Peru and other places. The ragged refugees had gathered bits of cardboard, tin and wood to build crude shelters. They had no water supply, no sewer, no electricity, and no security. Dr. Horner wanted to introduce me to some of the destitute families they were trying to serve in the shanty dwellings.

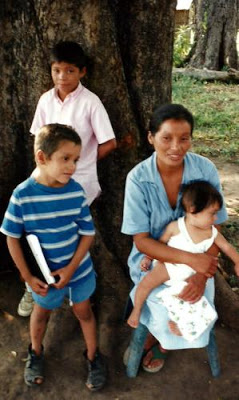

There were mothers with babies balanced on their hips, and children in tattered clothes. Toothless men with worn out shoes came to meet me. Dr. Horner was especially eager for me to meet one of the families he was helping. He had just recently been able to gather some wooden posts and a few pieces of sheet metal for a roof to protect Maria's little family from the rain.

Maria and her husband and children had lived on their little farm in the mountains. One day a marauding military band came to their farm and demanded all their eggs and goat milk to feed their troops. Later they returned and demanded the chickens and goats to slaughter and eat. Once again, the terrorists returned, put a gun to the head of Maria's husband and demanded that he join their insurgency group. When he refused, the soldiers lined up the family in front of their own humble house and killed the husband in cold blood as the children watched in terror. They told Maria and the children to leave. They would return by Friday, and if they were still there, they, too, would be murdered. Maria gathered her children and fled to San Juan Opico for refuge.

By the time Dr. Horner had found the mother, her children were literally starving. She had had only a single cucumber for them to eat in the two previous days. Dr. Horner gathered food and took it to the tree where Maria was living. After about three trips of taking food to Maria, a man slipped into the space about 4:00 a.m. where Maria and her three children slept, and put a sharp knife to her throat. He told her he was taking all her food that had been brought and demanded all other food that would be delivered to her in the future. She was warned that if she mentioned what had happened to anyone or did not comply, he would return unexpectedly at night and slit the throats of her children one at a time and, last of all, kill her. He told her his family had been there longer than hers and deserved the food ... he would provide for his hungry children ... even if it meant killing hers. Horner never returned to the woman's shanty to deliver food. Rather, he had the oldest boy, who now came to the orphanage school, take small supplies of food home each day in his school backpack.

I went with Dr. Horner to meet the brave young mother. He told her about me and about the medical clinic that would be able to give her children good health. Maria's eyes filled with tears. "Why would this man come here to help us?" She stood for a moment, overwhelmed. Then, making a sweeping hand motion toward her little family and touching each child on the head, she looked back at me and leapt toward me wrapping her small arms around me, sobbing, as she buried her face in my white shirt. I held her momentarily. As Dr. Horner and I walked away I looked down at my soaked shirt. I didn't want her tears to evaporate or disappear. I wanted to wear them as a badge of love. I prayed that somehow God would dispatch a small band of angels to care for and protect this little widow who had seen more of raw life than I would ever experience.

How Does That Happen?

The agent in Imphal, India came out to the steps of the small airplane, “I think you missed your flight connection in Calcutta, but check with them there and see if you can get a seat on the later flight into Delhi at 10:00 p.m.”

“But,” I protested, “My Thai Airline flight to Bangkok departs from the Delhi International Terminal and not the domestic terminal at 10:00 p.m. That won’t work even if I were early, and I am nearly two hours late!” He lowered his umbrella over his head and walked away in the rain. To make things worse, my Delhi flight from Calcutta was also delayed. I did not have a ghost of a chance to make the Thai Airline connection. My flight would leave at 12:05 midnight and I would be nowhere close by.

I stopped mid-step and prayed, “Oh God, I don’t usually hassle you about such trivia, but I really need help on this one. It wasn’t my being dilatory or sloppy or lazy or late on this one, but I’m in trouble. Please help me. I really need to get home to Denver.”

As soon as the plane from Calcutta landed in New Delhi I took off running for the terminal. They had not even opened the cargo doors of the plane. It was after midnight. It would take at least 20 to 30 minutes to get the luggage from the plane to the terminal, but I could get instructions in the meantime on how to get across to the other side of the airport runways to the International Terminal.

The luggage arrival room where the carousel belt was located was still dark as I went past. No one had turned on the lights and no one was yet in the room. I stopped dead in my tracks. From the corner of my eye I noticed a single bag on the idle luggage belt. Impossible! It was my luggage! There was no explanation for it being there. I grabbed the bag and made a dash for the entrance of the Domestic Terminal. I stopped long enough to ask a woman at a kiosk for the best way to get to the International Terminal. “Well,” she blurted, “it sure won’t pay you to take the free shuttle, it takes an hour, leaves on the hour, and has already left.” I found it would take me at least 30 to 40 minutes by taxi, depending on the traffic.

While standing there I noticed an Air India counter back inside of the security area I had just exited. I decided to go for it. I walked right up midstream through the throng of people pushing their way out of security.

The security guards, dressed in their military uniforms, got this puzzled look on their faces when they saw me boldly walking right back through the oncoming crowd into the security area. When one moved toward me, I just put up the palm of my hand toward him and smiled kindly at him. He stopped and just looked at me.

There was a man standing at the desk. “I need your help very desperately, sir,” I said. “Your plane was delayed form Imphal to Calcutta and now I will miss my international flight on Thai Airway to Bangkok. How can I get to the international check-in counter for Thai Airway?” He reached for the radio on his belt and at the same time said, “Follow me closely and bring your bag.” There was a van waiting for me. As we left I hollered out, “Please call Thai for me . . . Thank You!”

Our route did not take us 40 minutes, but took us right across and down the active runway with lights flashing. We hurriedly went through several military checkpoints with only a tootle of the van’s horn.

“I will take care of your check-in … you go with this lady! Had you been one minute later I couldn’t have done this.” It all happened so fast. I slumped into my seat, “Thank you, God!” How do things like that happen? Did an angel carry that bag? Did it fly through the air by itself? Did its molecules unassemble, then, reassemble on the baggage belt? I wonder a lot about what I don’t know!

It's O.k. to Cry

When Dr. Douglas Jackson was appointed as President of Project C.U.R.E. in October, 1997, I was freed up to concentrate on developing our international strategies and partnerships. We were receiving more and more requests to visit needy countries to perform the required Needs Assessment studies. We were then shipping into over 80 countries and donating to hundreds of hospitals and clinics around the world. Douglas, who was gifted at developing public relations and expanding financial resources, was also doing a superb job of developing the procurement process, and creatively growing the volunteer base. New methods were developed for inventory control and warehouse procedures.

It was getting to the place where I would be traveling to Asia, then coming home, reloading my suitcase, traveling to Africa, hurrying home, reloading my suitcase, traveling to South America, speeding home once again to reload my suitcase. I remember, on one occasion, being in northern Pakistan on the Afghanistan border where it was very cold and needing to then travel directly to Entebbe, Uganda and Burundi via London. The clothes I needed for the cold mountains of northern Pakistan were not the same clothes I needed for hot, sweaty Burundi. So, Anna Marie packed another suitcase for me with the appropriate clothes and supplies in it, jumped on an airplane as soon as her school was dismissed on Friday afternoon, met me in London, and we exchanged suitcases and off I went again.

I was seeing more filth and cockroach- infested hospitals, more pain and misery and death and dying, more frustrated and discouraged doctors and nurses, and more needless suffering and stark hopelessness in 30 days than most people would see in a lifetime.

A thousand times my heart would be broken. Many times in my hospital tours I would have to hide around a corner just to cry. I would feel absolutely helpless and torn after I would see a small child who had fallen into an open cooking fire, lying on a soiled and sheetless hospital pad covered with dirty bandages. What I would hear from the sincere, but frustrated, nurse would be, “But, Dr. Jackson, we just don’t have any way to treat burn patients at this hospital. The child will die soon.”

In Somalia, I had stood beside the rickety hospital bed of a young boy. The lad had inadvertently stepped on a hidden land mine that had been left over from the tribal wars, and hisleg had been blown off just above the knee. But the neglected hospital was not able to even perform a respectable amputation, because it had been months and months since the hospital had any suture to stitch shut wounds of any size. The chances were very high that the lad would not even live to be a cripple. I cried.

I was quickly learning that it was all right to cry about the things that surely were also breaking the heart of God.

My constant prayer was that God would protect me, but that, also, I would never get callused or cynical about what I was required to see day after day after day.

Source & Resource

By 1996 Project C.U.R.E. was shipping donated medical goods into 40 countries around the world. That year alone we had delivered 50 cargo shipping containers with a wholesale value of twenty million dollars into countries with desperate and hurting people including India, China, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, and new targets in Africa.

We even teamed up with Israel and donated over $1 million worth of urgently needed supplies to help cover the unusual demands caused by an influx of over 750,000 refugees from the old Soviet Union and Ethiopia into Israel. Most of the immigrants had come to Israel sick and without any money. We had stepped in and helped in their time of need. The positive reputation of Project C.U.R.E. was growing at a sprinter’s pace.

Where were we getting all the medical goods to ship? Could we keep up the pace with the ever increasing demands? How could we ever continue? Would it be physically possible to sustain what we had started in 1987?

One night in a grungy hotel room in the old Soviet Union I woke up in a dead sweat. I had just been with some wonderful doctors at a hospital where I was conducting a “Needs Assessment” study. My very being there had raised their expectations and hopes that I would approve them and send the needed medical goods to their hospitals and clinics. During the night when I was half-asleep, I nearly panicked.

What if, by my just being there, I had caused the doctors, nurses and government officials to believe that I was going to approve them and send all kinds of medical supplies and pieces of equipment, only to return home and find that I had nothing in my warehouses to send? Just what would I do? I would have been guilty of giving them false hope. I didn’t want to have any part of giving people false hope.

Then, a marvelous thing happened. Out of the darkness of that miserable night came a sense of calm and an assurance as if it had been an eternal declaration, “Don’t worry about how much inventory is in your warehouses. You just concentrate on getting the goods distributed to the needy people. I will always give you just a little bit more than you can ever give away.” I smiled in the darkness, rolled over and went soundly to sleep.

Now, fifteen years later, I walk through the Project C.U.R.E. warehouses and collection centers spread across the USA and marvel at the millions of dollars of life saving medical goods being processed and packed. Thousands of faithful volunteers are there loading the cargo containers to be shipped to the more than 120 recipient countries and thousands of needy hospitals and clinics. But I can still hear that soft, assuring voice saying, “You concentrate on getting the goods distributed to the needy people. I will always give you just a little bit more than you can ever give away.”

I needed the Resources, but I found there to be only one true Source! God is the source; everything else is a resource. God the eternal and boundless source has been flawlessly faithful in supplying to us the resources just at the very moment we have needed them.

Success

Remember back to the high school American Literature class where you were assigned to read Ralph Waldo Emerson’s words:

To laugh often and much; To win the respect of intelligent people and the affection of children; To earn the appreciation of honest critics and endure the betrayal of false friends; To appreciate beauty, to find the best in others; To leave the world a bit better, whether by a healthy child, a garden patch, or a redeemed social condition; To know even one life has breathed easier because you have lived. This is to have succeeded.

You were tracking fine through the “betrayal of false friends” stuff because your best friend had just been a real jerk before class. But when you got to the passages of leaving a “garden patch” or a “redeemed social condition” or especially the part of “one life breathed easier because you lived” the response was a smirk, a chortle and some rolling of the eyes! That was “SUCCESS?”

Then you left American Lit. class and went to the assembly where a high powered motivational speaker had been brought in to tellyou our space guys had just walked on the moon and the world was wide open for you to achieve, excel, get rich and be a success. And you beat on your chest and said, “Sorry, Mr. Emerson, you ain’t cool.”

Personally, I like to excel and achieve. And I have done my share of wealth creation and accumulation. But I find myself smiling at me with a much gentler smile these days as I set aside each year the week of April 15th to not only sign my tax returns but also dig out my lily patch from the Colorado snow. It’s a patch I carved out myself nearly 40 years ago that lies between the stone wall along the road and the sparkling mountain creek that runs through our property. It’s a wonderful garden patch.

There are also days now when tsunamis of overwhelming joy and contentment wash over my weary soul and make spring out of winter as I hear the simple “thanks” of a little Ethiopian girl in Addis Abba whose life was just saved with one of our donated pediatric surgery machines ... or the director of the University Medical Training Hospital in Brazil say, “Dr. Jackson, you have brought us millions of dollars worth of supplies and pieces of equipment but the thing that you brought that made the most difference was ... you brought hope to us.”

Mr. Emerson, sorry it took awhile to recognize and embrace your soft-spoken wisdom. I concede the debate to you and am thankful that I never forgot your words from that literature class.

Wealth Rooms

Snuggled up against the western borders of old Burma in the rugged front range of the majestic Himalayas, just south of the Bhutan and only a few miles from China, lay three orphaned sub-states of India. Because they are nearly cut off from the rest of India by Bangladesh, the territories of Mizoram, Manipur and Nagaland are characterized by dangerous insurgency and wild independence. I traveled there to assess some needy hospitals and clinics.

While in the city of Kohima, Nagaland, my host took me to a village near his birthplace. Before the missionaries had come to the area, the residents had been ferocious headhunters. The sturdy ceremonial wooden gates of the village had been carved and painted with scenes of warriors carrying the heads of their tribal enemies as trophies. No longer do they hunt down their neighbors. Now, heads of bear, deer, straight-horned bucks, monkeys, and wild boars are displayed on the roofs, porches, and outside walls of the homes.

Just inside the door of each village dwelling was a special room that immediately revealed the earthly wealth of the owner. Woven reed baskets nearly six feet tall were filled with rice, maize and other grains. Ears of corn were draped over the rafters and cuts of meat were hung from racks to dry.

My doctor friend interpreted as I talked with an old village resident who told me that the entry areas were called ‘Wealth Rooms.’ “It is good to be considered wealthy because it lets everyone know that you are not lazy, but very productive. You care about life. But the ‘Wealth Rooms’ serve an even greater purpose,” he told me.

“Later in life, when a man becomes rich and his room is very full, he invites all the other village people to his house for a ‘Giveaway Party.’ All his friends and neighbors come and honor him because he had worked very hard, had been a good hunter and had lived wisely.” At the end of the party the host goes to his ‘Wealth Room,’ takes the contents and divides them up among the other inhabitants of the village. In return, the villagers confer on the man and his family great honor and influence and guarantee him a legacy of greatness and respect and take care of him as long as he lives.”

I had never before heard of “Wealth Rooms” and “Giveaway Parties.” What a great way to move from “Success to Significance!” But I quickly agreed that the concept had certainly been established in heavenly wisdom. It had been both refreshing and confirming to realize that, way back in the ancient Mongol history, some folks had it figured correctly: “Your greatness is always determined by what you give away from your ‘Wealth Room’ while you are still alive.”

Helping the Unhealthy

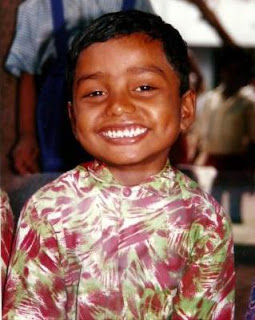

In a rural village outside Salem, India, Dr. Siddharthan tried to persuade Shanthi that he could successfully perform the needed eye surgery on her young son and make him see for the first time in his life. “I will send Samuel Stevens to the village and pick up you and your son. He will bring you to the eye hospital. Everything will be fine. Can you imagine how happy your son will be when he sees his mother for the first time? And the whole village will rejoice when they see the great miracle.”

“No,” said Shanthi softly as she lowered her head and stared at the ground. "I want my son to see, but the people of my village will not hear of any such thing. They have warned me that if you put a new eye into my son’s head he will be forever cursed, I will be cursed and my other children will be cursed.” Shanthi began to shake with fear. “My villagers demand that they like my son just as he is … blind. They want to take care of him all of his life. When he needs them to help him walk or eat it makes them feel very good and important. They want him to depend on them forever. They will not allow me to bring my son to your hospital.”

It was decided by Samuel Stevens and Dr. Siddharthan, however, that the day before the surgery Samuel would drive to the village and try to persuade Shanthi to allow the surgery to take place on her son. I was invited to go with Samuel and meet Shanthi and the villagers. When we met with Shanthi she began to cry openly. The previous night she had a dream. She saw a man come and take her son away and later he brought him back to the village … and he could see! She had never seen Samuel before but he was the exact man who had come in her dream for her son. “I do not need to come with you” she said. I know that when I see my son again he will see perfectly!”

And indeed, when he returned to the village, he could see perfectly. Oh, what a day of celebration!

On my airplane ride back from Salem and Coimbatore to Madras, India, I began to search my own heart. “Are there people or situations in my life where I am encouraging unhealthy dependence?” The villagers wanted Shanthi’s son to stay blind because it made them feel good and needed. What a tragedy that would have been. Who or what in my life do I need to relinquish in order for someone else to become healthy.

I did something...I made YOU!

During one of my trips through Asia a friend of mine shared with me an intriguing episode:

"Past the seeker as he prayed came the crippled and the beggar and the beaten. And seeing them, the holy one went down into deep prayer and cried, “Great God, how is it that a loving Creator can see such things and yet do nothing about them?”

And out of the long silence, God said, “I did do something . . . I made you.”

I am curious as to how our inherited culture has allowed for us to so inconspicuously and gracefully slide out from under the regard for personal responsibility and engagement. I sometimes catch myself asking with an air of entitlement, “Why doesn’t somebody, or the government, do something about all these glaring problems?”

I love working with entrepreneurs, be they economic or cultural entrepreneurs, because they possess a refreshing disposition of personal accountability. The very concept of “entrepreneur” embodies the notion of personal responsibility and accountability. I love it when an individual citizen steps up and says, “Yes, I can do that. I can come up with a solution to that problem. I can fix that so that everyone else is better off.”

Perhaps, the best-known social entrepreneurs are Bill and Melinda Gates, the founder of Microsoft, and his wife. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation funds many worthwhile causes, particularly in the fields of disease prevention and education. The Gates generation decided to use the expertise they had gained from the business world in addressing the world’s most intractable problems: poverty, disease, inadequate education, and corruption in government. They had learned the principles and effectiveness of economic globalization. Goods and services could be invented in the intellectual capitals of the world. The raw materials of these goods could be drawn from many nations, manufactured in others, and shipped around the world. The whole process could be tracked with uncanny precision by software that could put factories in Macao into overdrive when inventory ran low in Dubuque.

Marketing studies based on data mining or focus groups improved the development of goods and services, making the marketplace ever more responsive to peoples’ needs. Why not apply the principles that made the global market place so efficient to the world’s most difficult problems? Instead of the temporary fix of most humanitarian programs, why not use the tools of technology and global commerce to mitigate, or even solve, age-old problems.

The essence of social entrepreneurship—as with all entrepreneurship—lay in the reallocation of resources so that everyone would be better off. Our Project C.U.R.E.business model, for example, uses overstock medical goods to improve the health care of developing nations. Our collection, shipping, and distribution operations are prime examples of how to use economic globalization for good. The wave of social entrepreneurship that came out of the 1990s was a wonderful development. It reestablished in the public imagination that a person could do well in business in order to do good deeds in the world. It also spoke to the issue that God made us with a most unique possibility of partnership and accountability in the pursuit of discovering answers for today’s overwhelming needs.