(continued): Nagorno-Karabakh: August, 1998:Stepanakert was our destination. It is the capital of Nagorno-Karabakh and houses the country’s government buildings. The helicopter pilots gently set our ugly orange bird down in the midst of its own tornado and dust storm. When the chopper blades ceased rotating, a pilot named Uri opened the door, and we were allowed to crawl out. The air was hot and muggy, and there was no breeze at all after the helicopter’s windstorms died down. Vans were at the airport runway to meet us at Zori’s prearranged direction. I already perceived that Stepanakert is a lot different than Yerevan. There was something of bleak solemnity that permeated the spirit of the city. I could feel it. No one smiled. The expressions on people’s faces showed neither happiness nor pleasantness; rather, their facial muscles drooped, which had the effect of making their eyes look even sadder.

Our vans and taxis rendezvoused at the government buildings in the center of Stepanakert. The hotel in which four of us are scheduled to stay is only one block away from the main government building. I grabbed my luggage and went quickly with the others to get checked into our rooms and freshen up a bit before our scheduled 5:00 p.m. meeting with the minister of health.

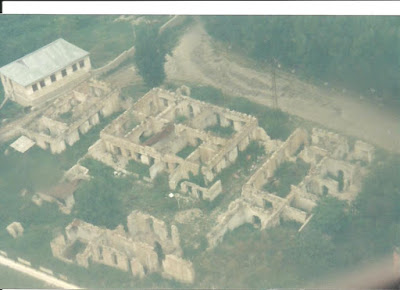

The hotel had known its days of glory and splendor in the past, I was certain. But that must have been over a hundred years in the past. Since then, I don’t think any maintenance had been performed at all. In addition, the building had taken some direct hits during the bombings of the past few years. As we entered, I looked up to the ceiling of the lobby area and marveled at the half-destroyed remnants of crystal chandeliers hanging precariously from the ceiling. Most of the crystal pendants were missing, and the few that remained closely matched in color the tarnished brass of the fixture. I guess I should have just kept focusing on the broken chandeliers, but I made the mistake of looking around at where we were expected to stay. Most of the rooms were uninhabitable, with collapsed plaster ceilings or broken walls or doors. I recalled all the terrible places around the world where I had been expected to lay my head down and sleep, and at first I figured I would just take a deep breath and make the present situation work.

A pudgy, unkempt woman met us as we came in and handed us a couple of keys. She then accompanied us to our rooms on the third floor. On our way upstairs, I began to notice that the hotel wasn’t just old and war damaged; it was grossly filthy. At the door to one room, the unpleasant innkeeper communicated to us in Armenian that she expected three of us to stay there. But there were only two beds. We protested, but she countered by showing us that it was the only room in the hotel that had its own bathroom. We stepped in to have a look-see—we shouldn’t have. She lost her sales point. The bathroom was a terrible fright. The floor had been torn up and not repaired, so there were piles of dirt and broken concrete to sidestep. The mirror consisted of just a few broken chunks that still stuck to the wall. The sink was crusty, but we were to discover that this didn’t count for much, since there was no running water available on floors two and three. Obviously the toilet wasn’t of much use, since there was no running water. But they had tried to compensate for that by filling the dilapidated bathtub with some drain water they had carried up in a rusty bucket and dumped.

I made signs to the lady as if I were turning on and off a water spigot, and hand motions as if I were taking a shower. She cracked about a half smile and pointed back down the stairs. We all then communicated to her that we wanted to see the running water downstairs. After all, we were going to be here the major portion of a week! She pointed to her watch and indicated that there would be no water even downstairs until after 5:00 p.m. We insisted on seeing the shower room anyway. I will let your own imagination paint the picture of what we found there.

Thinking we had no other options, we put our suitcases in the rooms, and as we walked down the stairs and out the door to our meeting with the minister of health, Dr. Scott Stenquest, Dr. Anthony Peel, and I talked about perhaps using the old sofas in the lobby as beds.

Our meeting with the health minister, Dr. Aleksander Petrossian, really got our visit off on the right foot. There was an instant bonding between the two of us, and I knew I would be able to work with him in the future. I explained to him all about Project C.U.R.E., why we had come, and how the needs assessments would be conducted in his hospitals with his cooperation and blessing. I was then perhaps a little more stern with the health minister than I needed to be in explaining my expectations for getting the containers into the country and the distribution process.

While I was laying down my points in no uncertain terms, I had a flashback of my presentation in a similar situation in Benin, West Africa, when my snippy, little Baptist missionary, who had never had a meeting with a government official higher than the local traffic cop, chided me and told me I had no right talking to a cabinet minister in that tone of voice. Pushing that picture aside, I kept up with the pressure. I was demanding written assurances of getting the medical goods into the country without customs hassles, levied taxes, or transportation delays. I also demanded the right to distribute the goods as we see fit based on the findings of our needs assessment and not based on political determinations. I joked with him just enough to keep him smiling and his head going up and down.

I asked the minister to give me wise counsel as to which hospitals we should visit and in what order. He agreed that by Monday morning at 9:00, he would have all the answers ready for me, and the hospitals notified of my arrival.

At 7:30 p.m., Zori Balayan ushered our delegation into the office of the prime minister of Nagorno-Karabakh, Zhirayr T. Poghosyan. Baroness Cox was extremely gracious in her introduction of Project C.U.R.E. to the prime minister. We only had time to greet Mr. Poghosyan with a few words, because he had pulled himself from another scheduled meeting to meet briefly with us and greet us. It is certainly helpful having Zori make sure we receive our requested appointments with any of the government officials.

Dinner was scheduled at 9:00 p.m. in the lower level of the government building. At dinner Zori told us that this is Lady Cox’s thirty-ninth trip to Nagorno-Karabakh. I have watched in amazement while we have been in Armenia and Karabakh at the recognition and reception the local people give to Baroness Cox. Everyone knows her, or at least who she is. To them she is almost a patron saint. She was there all during the war and held nothing back within her ability, giving aid and comfort during the people’s darkest hours. My respect for her has grown by the day. She really has a gift of love for the oppressed and particularly those of the persecuted Christian church. I am not surprised in the least that she has been given nearly every international humanitarian award for her spirit and her work.

Next Week: Mountain Top Banquet

© Dr. James W. Jackson

Permissions granted by Winston-Crown Publishing House