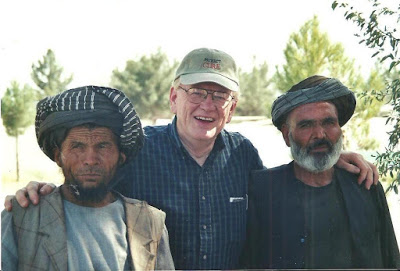

Afghanistan: August, 2002: Our bus left the refugee area and we were driven back to the warlord’s enclave. Everyone got off and went into the heavily guarded headquarters where Commander Chief Miramza met us graciously. We were seated once again and additionally fed ripe watermelon slices and freshly picked grapes. The commander seemed genuinely appreciative of our having made the effort to help the people. It’s just that you never really know where their true loyalties lie. Maybe he was happy that the Taliban had been dislodged from power in his area and maybe Bin Laden may have been his hero. There was just no way of telling. You just never knew whose side he might figure that “Allah” was on.

I remembered that back in Tashkent during my meeting with the embassy folks they had told me a supposedly true story of an incident that had taken place during the American bombing raid. They told me that a Taliban tank operator was sitting on top of his tank watching the absolute precision of the American bombing operation. The bombs would travel along the ground ripping deep trenches in the ground then find their way exactly to the pinpointed target and completely wipe out the designated object.

He watched the precision operation for several days, turned to his Taliban buddies and said, “I was told specifically that Allah was on our side and assuredly he would give us the victory. But, I don’t think so.” And thereupon he jumped down from his tank and walked home.

We pulled out of Balkh and drove back toward Mazar-e Sharif. It was early evening when we returned to the Young Nak compound. The showers there were nothing to brag about but the wetness of the water washed away the desert dirt and soothed away the emotional afternoon. God’s faithfulness had protected us once again.

After dinner it began to cool down a bit outside. It was so hot at night that we just laid on the mat and sweat. As I had mentioned earlier, fortunately, our room was equipped with a fan.

To keep the mosquitoes and other insects from attacking our totally unprotected bodies, the manager of the Young Nak compound delivered each night to each room a burning citronella coil that stayed lit like a punk and burned slowly throughout the night. He set the punks in the windowsill, which was made of concrete, and no one worried about safety but simply enjoyed the mosquito-free atmosphere.

Monday, August 5

About 1:30 a.m., I was startled as I caught a glimpse of a figure running in the darkness out of our room. My eyes bounced open and I was wide awake. I sat up and reached for my little flashlight, which I had lying on the sleeping mat next to my head. I quickly turned on the light and realized that the room was engulfed in a heavy layer of smoke.

The sleeping pads had been situated on the floor adjacent to the room’s walls, around the entire parameter of the room, except where the door was located. I was sleeping on the pad on the same wall as where the door was located. My head was in the corner and my body stretched toward the doorway. The mat that was at a right angle to my head was placed right under the low positioned window. Jason was sleeping exactly opposite the room from me and Mr. Kim was on the floor opposite the window. Toward the end of the mat, which was under the windowsill and at a right angle to my head, I could see a patch of flames about three or four inches above the surface of the mat.

About that time Jason jumped up and we got to the hot spot at about the same time. The coverlet on the mat was ready to erupt into full flame. The mat itself had burned most of the way through and had reached a kindling temperature sufficient to launch it into full flame.

Immediately I started pulling my things off the mat. I had placed my travel bag, my camera, and other items on the mat next to my head. If the flames had erupted they all would have ignited quickly.

It had been Mr. Kim who first realized that we had a fire. And it was he who had run out of the room to get some water. Soon he came running back into the room with a supply of water and thoroughly doused the fire. Jason and I then grabbed the mat and hauled it outside just in case the fire was not totally extinguished.

Another Korean man who had been sleeping upstairs had also come to the room sensing that there was a fire. The smoke coming from the mat had been toxic and once the episode was over I realized that it had affected my lungs as well as my vocal chords.

The thing that bothered me most about the mishap was that I had not awakened at the strong smell of the smoke. I had awakened at the man running out of the room. It certainly was no mystery as to what had started the fire. The fan had blown the window curtain just right to flip the mosquito-repellent punk off the windowsill and onto the mat. I guess my subconscious mind had accepted the fact that there was supposed to be smoke from the punk and didn’t let me know the difference between the burning citronella and the toxic smoke from the mat. Had I been by myself in a room somewhere in one of the other countries where I traveled, I might not have awakened before the mat burst into flames. Once more, God had been faithful to protect us.

It seemed like a short night after that, because we had to be up at 4:30 a.m. in order to get ready to leave on the bus.

On Monday we would reverse the trip that had taken us into Afghanistan as we traveled back to Uzbekistan. We left Mazar-e Sharif and drove through the sand dunes that had blown their way back over the road. We cleared Afghanistan border control and made our way across the bridge that joined the two countries over the Amu Darya River.

It was actually more difficult getting back into Uzbekistan than it had been getting into Afghanistan. There was a tremendous amount of drug traffic out of Afghanistan. Production of heroine in Afghanistan topped nearly all other countries in the world. Therefore, they very carefully check not only the travelers and their luggage but pay particular attention to the large and small trucks that cross the border and the automobiles. I was surprised, however, to see drug-sniffing dogs employed at the Uzbekistan border working to detect the chemicals.

Tuesday, August 6

Tuesday morning was an informal training session for Jason on needs assessments. Anna Marie and I met with him for a couple of hours reviewing observations and situations that had taken place on the trip. Jason was an eager learner and had really become a committed and loyal member of the Project C.U.R.E. team. I had become impressed that he would be able to handle international assessments for Project C.U.R.E. in various venues around the world.

At noon Daniel Kim came to get us checked out of the hotel and delivered to the airport. We had a good opportunity to discuss the findings of our assessment studies with Daniel Kim and suggest the logistics and details of the medical shipments from Project C.U.R.E. into Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. It was going to be an exciting project to see what we could do together with the Koreans in Central Asia.