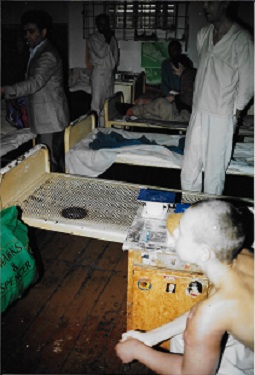

I thought you might enjoy peeking in on what it is like to try to ship and deliver a 40-foot ocean going cargo container of medical goods into a developing country. Let’s try Senegal in western Africa. Keep in mind that Project C.U.R.E. will deliver approximately 180 such containers - just this year - into needy 3rd World hospitals.

(Dakar, Senegal: October, 1999:) I’m headed back to Dakar for the third time in a year. Based on my earlier needs assessment, our Denver Project C.U.R.E. people gathered the appropriate medical goods and sent them on their way to Houston by rail and then by ship across the Atlantic Ocean to the Port of Dakar. I was asked to return to Dakar in October and make a formal presentation of the unprecedented gift of medical items to health and government officials. The people of Senegal want a special ceremony because in the history of the West African nation, no organization has ever brought a medical team to serve and then given such a generous gift of love. The value of Project C.U.R.E.’s investment in dollars, including both the medical team and the container load of goods, was well in excess of half a million dollars.

Mohammed Cissé and his brother Dr. Cheikh Cissé met me as I walked down the ladder from the plane in Dakar. Dr. Cissé and Mohammed almost seem like family to me now that I’ve visited Dakar three times in one year.

Monday, October 4

Today proved to be another lesson for me in Third World bureaucracy. It’s so easy to get accustomed to America’s service-oriented business environment. But most of the world’s business still runs on seventeenth-century concepts and methods. This is especially true of Africa. Our objective today was to complete the necessary paperwork and transactions to clear the Project C.U.R.E. cargo container through customs and the Port of Dakar so it will be available for the presentation ceremony later in the week.

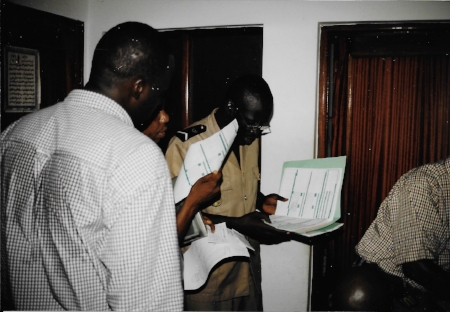

Mohammed and I left the hotel after breakfast and walked to the main government building, which houses the ministry of health. I had met Senegal’s minister of health and his main staff people on previous visits. The man highest in rank under the minister holds the position of administrateur civil principal. He is the chief decision maker who makes things happen, or not, in the country’s health-care system. Mr. Makhtar Camara currently fills that position.

Mr. Camara has a military background, but he warmed up quickly and genuinely expressed his appreciation for Project C.U.R.E. coming to Senegal to help. Mohammed and I were ushered into the office of the health ministry’s finance director, where we met Ousmane Ndong. We discussed the necessity of declaring the container load exempt from any tariffs or duty obligations, since it’s a humanitarian shipment. Mr. Ndong agreed with the exemption request. We also discussed the possibility of his office securing a large truck to deliver the container from the docks to the national pharmacy warehouse in Dakar and distributing the donated goods to the individual hospitals and clinics. He agreed to try to find some funds to help us.

At 11:15 a.m., we found out that the paperwork for the container had already been messed up. Customs had presumed that the cargo contained donated pharmaceuticals and had sent paperwork somewhere for review and to test the goods. I called their attention to the official shipping manifest that clearly stated the load contained only consumable medical supplies for the hospitals and clinics, such as needles, syringes, catheter tubes, latex gloves, and so on. We then had to go on a wild-goose chase to retrieve the papers.

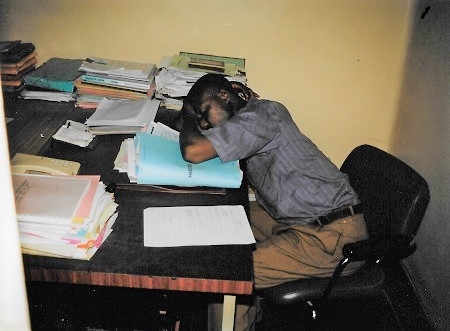

Once the paperwork was back in our hands, we had to begin the process all over again. The processing system Senegal employs is terribly archaic. My closest guess is that we had to go through thirty individuals to clear the shipment, and each had to inspect the paperwork and hand-record the information separately in his own book.

If they found the least little problem, real or perceived, they sent us back to a previous bureaucrat or to a new set of paper pushers. If they could send us away, it would keep them from having to enter all the information by hand in their books and give them an excuse for exercising their authority. It was a most disgusting and frustrating process.

The ministry of health, or santé, gave us a full-time assistant, El Hadji Owague, to help us through the process. It even took him a full two days to run through the maze, and most of the bureaucrats along the way were his everyday acquaintances. El Hadji is one of Mohammed Cissé’s former schoolmates and close friends. He told us that it would normally take weeks to process the paperwork, and we were expecting to get it finished in two days!

From the health ministry we went to customs. It too was a circus. From customs we went to the port authority in downtown Dakar. We encountered a problem there and had to retrace our steps to the health ministry for more approvals and big red stamps. The port authority had lost their part of the paperwork and accused us of never giving them any copies. After visiting three different offices, we proved by the numbers in one of their books that they had indeed received the paperwork. But no one wanted to get involved in finding the papers. Finally, we found them on one bureaucrat’s desk, but he wasn’t in the office to sign off on them. No one else wanted to take the responsibility to process the papers, so Mohammad, El Hadji, and I found a little restaurant and had a typical lunch of rice and fish before resuming our wild-goose chase.

Before the day was over, I got weary of climbing broken concrete steps in buildings, where the grimy walls were all painted a government yellow, and walking down hallways of broken and missing tiles. Mohammed and I began to joke about how to gauge the importance of the men in the offices by whether they had fans on their desks, real air conditioners in their windows, or nothing at all.

Finally, in the late afternoon, we made it through the processing and headed to an old building crammed with unused United Nations UNICEF trucks. The man there was a forwarding agent or broker. He didn’t even have his paperwork right, so we had to retrace our steps to get him caught up. I told Mohammed and El Hadji that I would bet the United Nations didn’t even remember that their UNICEF trucks were parked in the old building. Another international UN bureaucrat had probably put them in there and then moved on to Zimbabwe or Somalia.

Before we finished for the day, we returned to the office of the port-authority chief three different times, and three different times we returned to Mr. Camara’s office, plus all the other lines and offices. During one visit back to Mr. Camara’s office, the health ministry planned out the presentation ceremony and location and wrote up a press release for the Dakar newspaper. The officials are genuinely desirous of putting together a respectable occasion to receive the over one-half-million-dollar gift from Project C.U.R.E.

Tuesday, October 5

This morning Mohammed, El Hadji, and I again walked from the Novotel hotel through the narrow streets to the health ministry, avoiding the snarled traffic in the roadways. El Hadji picked up our paperwork, and the health ministry gave us a van and a driver to take us out to the port authority offices, where the container was being stored.

I thought our maze running was over, but I was mistaken. We did bump the quality of the maze up a notch or two, because nearly all the offices there had air-conditioning and even some computers. The big difference was that we were now dealing with a shipping, storage, and forwarding company, which actually handled the containers. Their operation ran a little more efficiently because there is a bit of profit involved in the international process, and people who mess up or just don’t show up for work, which is typically the case with government workers, get fired from their jobs.

Along with the profit aspect, the men at the port office assessed a fee that had to be paid before they would release the shipment. The shipment arrived in Dakar on September 18, but no one in Senegal did anything to get the paperwork process moving until we arrived. By the time we hit the storage area, where the container was physically held, the agents informed us that we had exceeded our grace time, and we would have to pay for two days of storage. I was finally able to talk the top man, chief of port Elimane S. Gwingue, into waiving the charges when I showed him the original Declaration of Donation certificate, which I just happened to have in my attaché.

But the officials still needed funds to move the container from the port holding area to the national pharmacy warehouse. So back we went to the director of finance at the ministry of health to beg for the money.

A little after 6:00 p.m., Mohammed and I arrived at the storage lot and prodded the workers to load our container on a trailer and hook it onto a big semi-truck.

Then Mohammed and I crawled up into the cab of the big truck and actually rode with the drivers to deliver the container to the warehouse in a shanty part of the city. Dinner tonight tasted good, and the hotel bed felt wonderful.

Next Week: USA Culture Shoc